- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

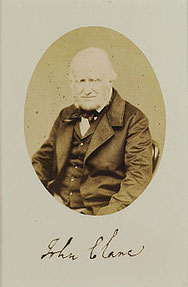

John Clare's Journey

(First published by www.independentleft.ie)

The poet John Clare was born in 1793 on the day Jean-Paul Marat, the zealous Jacobin revolutionary who believed that “man has the right to deal with his oppressors by devouring their palpitating hearts”, was assassinated. He died in May, 1864, a week before the United States Congress formally recognised the Montana territory of settlement – in a region long-inhabited by Crow, Cheyenne and Blackfeet indigenous peoples – as Union and Confederate forces waged bloody warfare in Virginia and Georgia over the question of American slavery, its legitimacy and continuation. Throughout his adult life, Clare disapproved of those he called “the French Levellers” for the violence and upheaval of their programme, and he never left England, but his poetry nonetheless stands in an oppositional relation to the dispossessions, divisions and labours of the nineteenth century, the age of capital.

In contrast to the majority of his literary contemporaries, Clare, born in Northamptonshire to a family of tenant farmers, experienced the privatisation of common land that swept across Britain in the wake of the 1801 Inclosure Consolidation Act, converting communally tended landscapes into real estate, while intensifying the precarity and dependency of an entire population of rural workers. “There once were days, the woodman knows it well”, Clare writes, “When shades e’en echoed with the singing thrush”:

There once were lanes in nature’s freedom dropt,

There once were paths that every valley wound –

Inclosure came, and every path was stopt;

Each tyrant fix’d his sign where paths were found,

To hint a trespass now who cross’d the ground….

The Enclosure acts were presented by parliamentary advocates as a form of “improvement” in land law and distribution. Clare, however, perceived first-hand the violence of the new order, resulting in an entrenched disparity of privileges and resources, forcing newly created “parish-slaves” to “live [only] as parish-kings allow.” “Enclosure came, and trampled on the grave / Of labour’s rights”, Clare resoundingly asserts, “and left the poor a slave.”

In the work of William Wordsworth, the foremost ‘Romantic’ of the era (and later, Queen Victoria’s poet laureate), the natural world is celebrated and explored primarily as a metaphor for “the mind of man” – with all the gendered connotations of that concept intact – and indeed as a screen on which the artist’s own life and fancies are projected and presumed as universal truths. Even the relatively radical (if also aristocratic) George Gordon Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley follow Wordsworth’s lead in this respect, albeit with the more combative aim of inspiring political and individual regeneration through a renewed apprehension of natural cycles: the revolving weathers of the world coming to symbolise the human capacity for agency and change. Clare’s work, however, is of a different variety and intensity: an intimate, achingly powerful poetry of natural and social portraiture, grounded in both literary and vernacular traditions, as well as the earth- and sky-scapes of his native locale. His landscape poems have a luminous observational precision, as well as a rambler’s colloquial flow:

[A] wind-enamoured aspen – mark the leaves

Turn up their silver lining to the sun,

And list! the brustling noise, that oft deceives,

And makes the sheep-boy run:

The sound so mimics fast-approaching showers,

He thinks the rain begun….

Clare’s biographer, Jonathan Bate, has drawn attention to the poetry’s oral character and technical ease, while also noting Clare’s preservation of local melodies (for the fiddle-playing poet, a kind of pleasure) as an added dimension and possible source of the famed musicality of his verse. “The clock-a-clay is creeping on the open bloom of May, / The merry bee is trampling the pinky threads all day”, reads one poem, “And the chaffinch it is brooding on its grey mossy nest / In the whitethorn bush where I will lean upon my lover's breast”. As a young man, Clare in fact filled two notebooks with transcriptions of “gypsy” tunes and dances. His instinct, then and throughout his life, was to celebrate and learn from the richness of those folk cultures that fringed the world he grew up in, which (as Tom Paulin reminds us) was “no backwater”, but very much alive with its own artistic and intellectual customs.

“My life hath been one love – no blot it out”, Clare urges: “My life hath been one chain of contradictions”. And so, if he was cautiously conservative in his formal politics – rejecting what he viewed as the historical extremism of both French and Cromwellian revolutions – his respect and affection for the “gypsies”, as well as other groups who suffered disdain and marginalisation from English officialdom, are arguably more indicative of his fundamental social sympathies. “Everything that is bad is thrown upon the gypsies”, he writes despairingly of the prevailing attitudes in the Northampton press: “their name has grown into an ill omen and when any one of the tribe are guilty of a petty theft the odium is thrown upon the whole tribe.” Countering this trend, in his poem, “The Gipsey’s Song”, Clare adopts the voice of the travellers themselves, whose vagrancy and “liberty” (not to mention, their music) he admires.

And come what will brings no dismay;

Our minds are ne’r perplext;

For if today’s a swaly day

We meet with luck the next.

And thus we sing and kiss our mates,

While our chorus still shall be –

Bad luck to tyrant magistrates,

And the gipsies’ camp still free.

As here, Clare's rhythmic, vibrant verse is also a form of subtly layered social observation. “Religion now is little more than cant”, he writes in another piece, blending satire and poetic rage at the sight of “Men” who

… love mild sermons with few threats perplexed,

And deem it sinful to forget the text;

Then turn to business ere they leave the church,

And linger oft to comment in the porch

Of fresh rates wanted from the needy poor

And list of taxes nailed upon the door[.]

In a few lines, Clare exposes the entire edifice of hypocrisy and greed undergirding Britain’s burgeoning bourgeoisie, as represented by the “business”-oriented land-holders in the local parish. Tellingly, once again, the poem’s critique is made from the perspective of “the needy poor”: a recurring feature of Clare’s work, which repeatedly voices solidarity with those in his society for whom poverty, eviction, exploitation are palpable and perennial realities. Indeed, he writes as one of them:

O winter, what a deadly foe

Art thou unto the mean and low!

What thousands now half pin’d and bear

Are forced to stand thy piercing air

All day, near numbed to death wi’ cold

Some petty gentry to uphold,

Paltry proudlings hard as thee,

Dead to all humanity.

The acute, eye-level understanding of both social relations and seasonal change is part of what makes Clare so unique a figure in the Romantic literary movement. E. P. Thompson designates him “as a poet of ecological protest” on this basis: an artistic consciousness almost preternaturally attuned to the “threatened equilibrium” of the rural world – shaped by long-standing customs of free movement and shared access to natural space and resources – into which he was born: an equilibrium “Enclosure” definitively ended.

Importantly, Clare’s poetic conscience seems always primed to detect and diagnose cruelty as such, whether with regard to the victims of social “improvement” or more broadly. “The Badger”, for instance, offers a compelling (and somewhat brutal) portrayal of baiting day, a village tradition Clare himself thought cruel and disturbing. Indeed, the poem seems propelled by a pained identification with the torment of the titular animal, up-rooted from its den and eventually routed in the street by a crowd “of dogs and men”. It finishes:

Though scarcely half as big, demure and small,

He fights with dogs for bones and beats them all.

[...] He tries to reach the woods, an awkward race,

But sticks and cudgels quickly stop the chase.

He turns again and drives the noisy crowd

And beats the many dogs in noises loud.

He drives away and beats them every one,

And then they loose them all and set them on.

He falls as dead and kicked by boys and men,

Then starts and grins and drives the crowd again;

Till kicked and torn and beaten out he lies

And leaves his hold and cackles, groans, and dies.

“Poetry is the image of man and nature,” Wordsworth had declared in the preface to Lyrical Ballads (1800), “a homage paid to the native and naked dignity of man.” Far from idealising humanity and nature (and the relations between them), however, Clare’s ecological sensitivities and “customary consciousness” together helped him to depict life as he found it, and with a realism few other writers were socially equipped or emotionally inclined to engage.

Famously, Clare spent the last twenty-three years of his life at what was then the Northampton General Lunatic Asylum, having previously been hospitalised in a similar institution in Essex (his wife, Patty, and surviving children, remained in the family home in Northborough). As Bate notes,“Clare was perceived as an anomaly within his culture” – throughout his career, and after – with the result that there has “always [been] a tendency to attach labels to him: mad poet took over where peasant poet had left off.” Such classifications have obscured the achievements and concerns of the work itself, while also reducing the artist to a cliché (and a potentially harmful one at that). At any rate, Clare continued composing poems throughout this time: cataloguing personal spells of both depression and nostalgia, as well as producing erudite and witty works in the style of Byron (Clare claimed to have been and/or known a number of prominent world figures, including Byron and Napoléon Buonoparte). “I am–yet what I am none cares or knows”, he says in this period,

I am the self-consumer of my woes,

They rise and vanish in oblivious host,

Like shadows in love’s frenzied stifled throes

And yet I am, and live–like vapours tossed

Into the nothingness of scorn and noise,

Into the living sea of waking dreams,

Where there is neither sense of life or joys,

But the vast shipwreck of my life’s esteems;

Even the dearest that I loved the best

Are strange–nay, rather, stranger than the rest.

Clare's poetry, with its ecological critique and lucid music, is also knotted through with psychic anguish. A similarly potent atmosphere of sadness and isolation looms in another late, autobiographical piece, one of his greatest works: The Journey out of Essex. The prose letter was written as a personal account of his spontaneous departure, in the summer of 1841, from the asylum where he had been admitted as a patient, heading for Helpston in search of his first love, Mary Joyce, who was in fact deceased by this time. It was a four-day journey of “hopping with a crippled foot” in “old shoes [that had] nearly lost the sole”, with little food or water, during which he slept out-of-doors more than once, including in a sodden ditch. “I was very often half asleep as I went on the third day”, Clare writes (with a characteristic minimum of punctuation), “I satisfied my hunger by eating the grass by the road side which seemed to taste something like bread I was hungry & eat heartily till I was satisfied”. In itself, the combined vividness and loneliness of the text makes for haunting reading.

The Journey also quivers, however delicately, with the pulse of history-at-large. It is difficult not to trace in Clare’s chronic hunger and homelessness, the crippling pain of his ninety-mile trek – expressed with unparalleled literary intensity – the spectres of alienation and displacement that accompanied Britain’s industrialising drive and imperial rule throughout the nineteenth century. In a chronicle written in the late 1830s, after two tours of the island, French magistrate Gustave de Beaumont noted how “every year, nearly at the same season [the] commencement of a famine is announced in Ireland”: a pattern of colonial mismanagement and market-exacerbated scarcity that would reach a new nadir of devastation in the mid-1840s, following the failure of the potato crop. In the same period, hundreds of thousands of peasant and labouring populations from Ireland, and across Britain and Europe, sailed to America in search of a more secure future, often in turn forcing indigenous tribes into conflict or internal migration. When viewed against such a world-historical vista, Clare’s desperate meal of roadside grass, his powerful yearning for home (which is, for him, both a physical place and a memory of a time, now lost, before enclosure), seems almost a parable of universal dispossession, in a century of civilised disasters.

“Oh, who can tell the sweets of May-Day’s morn / To waken rapture in a feeling mind”, Clare asks his readers: celebrating not only the turning seasons or his own sensations, but the joy and “plenty” promised by the specific community-in-nature he knew in his youth, and which in later years he hoped always (at times despondently) to reclaim. Clare’s poetry is one expression of that elusive but palpable awakening. Our politics might be another, drawn from nature, from rapture, from one another, and (as historians like Peter Linebaugh have contended) from May-Day itself, both a political and a seasonal tradition. If a future commons is possible, it begins now, with Clare: as we shape our lives and relationships through labour, song, compassion and respect. These are the actions by which we make the world.

Further Reading:

Jonathan Bate, John Clare: A Life

John Clare, Major Works

Tom Paulin, Crusoe’s Secret: The Aesthetics of Dissent

Minotaur

E. P. Thompson, Customs in Common