- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

Movie Miscellany: 8 (Athena, In a Lonely Place, The Jericho Mile)

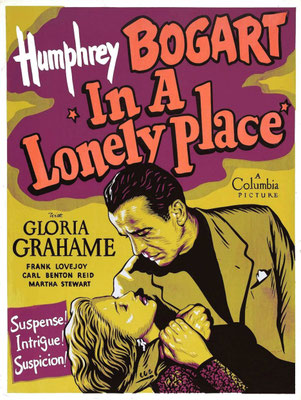

In a Lonely Place (dir. Nicholas Ray, 1950)

In Nicholas Ray’s best films, characters are engulfed (or stymied) by sexual passion, only to find themselves teetering on the edge of madness or chaos – giving rise to melodramatic narrative leaps, and a host of singular performances. Rebel Without a Cause (1955) famously established James Dean as an icon of troubled youth, provoked into acts of resistance and self-sabotage by the social conformities saturating mid-century American life. In Johnny Guitar (1954), the action is splashed and tinged by garish colours (mostly, as in Wim Wenders’s later Paris, Texas (1981), roiling greens and reds), a chromatic carnival that heightens the pained elegance of Joan Crawford and Sterling Hayden, the two leads, as they pace together in their mortal dance. Preceding both of these films, In a Lonely Place (1950) features a cadaverous, and at times plausibly maniacal, Humphrey Bogart as Dix Steele, a washed up Hollywood screenwriter and war veteran, suspected, ambiguously, of murder. Dix is wry, jaded, mercurial, and magnetic, inspiring devotion and fascination in the people who surround him (one of whom, an alcoholic, “speaks but poetry and borrows but money”); this despite his habit of combusting into sudden rages that leave the room a-tremble. Among the quivering witnesses, and occasional victims, of such episodes is Laurel, his neighbour, alibi, and now lover, played by the magnificent Gloria Grahame (who was, herself, tumultuously married to Ray for a period). With a mixture of grace and quiet torment, Grahame embodies perfectly Laurel’s internal conflict: between loyal affection for Dix and a recurring, fearful concern as to his sanity and innocence. Her performance is reason enough to revisit this captivating investigation of obsession and moral doubt in Hollywood: that glittering theatre where dreams are made to shine, while dreamers wither in the shadows off-stage – wounded, wounding, and alone.

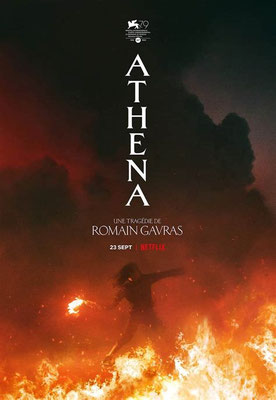

Athena (dir. Romain Gavras, 2022)

In October, 1961, two decades before Romain Gavras was born, and when his father, Costa-Gavras, had yet to embark on his own career as one of Europe’s foremost political film-directors, police in Paris attacked a crowd of Algerian demonstrators, beating dozens of protestors to death, and throwing others into the river Seine, where they drowned. At least 40, and possibly as many as 300, were killed, and the event, although the subject of an official cover-up, became known as ‘The Paris Massacre’. Today, it’s remembered as a brutal domestic incident within a much larger campaign of repression, torture, and colonial warfare against the FLN, a campaign that cost over a million Algerian lives, but which eventually ended with France ceding independence to its former colony. So when centrist politicians sound the gong of a punitive secularism (laïcité), or when far-right organizations unleash their openly Islamophobic and racist diatribes, we might recall the long, abusive history on which such discourses are based: for all its regressive cruelty and delusion, colonial nostalgia dies hard. This may be why Gavras’s seething tragedy feels at once as profound and startling as it does; as with co-writer Ladj Ly’s powerful Les Misérables (2019), it dares to confront the savageries of the grand republic from the dissident margins, which quickly become the centre of our world. Sustaining a febrile clarity from start to finish, given grit and momentum by a series of virtuosic tracking shots that pay tribute to the full vitality of the local tower blocks where the fighting begins, the film traces the fate of three brothers trapped in the banlieues as civil war explodes (and they themselves are shredded by grief and fury) in the aftermath of their youngest sibling’s murder, reputedly by police. From its opening scene, Athena balances intimacy (with the anger and suffering of its protagonists) alongside a ferocity of political perception, as the volcanic violences of France’s past and present erupt before our eyes.

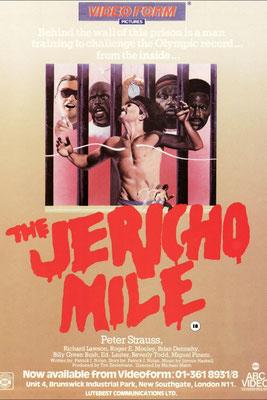

The Jericho Mile (dir. Michael Mann, 1979)

On first glance, The Jericho Mile seems a straight-forward character study: Larry ‘Rain’ Murphy (Peter Sturgess), serving a life-sentence for homicide, recovers a sense of selfhood by running laps in the prison yard, where racial tensions are rife; soon, he attracts the notice of the authorities, who believe they may have discovered a prodigious athletic talent. From such an apparently simple premise, Mann evolves a multi-layered representation of a wider system, built, we come to see, on exploitation, social exclusion, and brute force. In this, the film anticipates Mann’s later biopic of Muhammad Ali (2001): the initial subject matter, portraying the struggle of a flawed but honourable athlete in trying circumstances, gradually expands to encompass the tensions and political divisions of society as a whole. One of the movie’s most stirring scenes is when the contending ethnic groups create a “United Front Labour Brigade & Militia” in opposition to the gang of white supremacists led by Dr. D (Brian Dennehy), hitherto intent on preventing the construction of a racing track adjacent to the recreation area, which would allow Larry to compete at a national level while still serving his sentence. Here and elsewhere, the film is animated by a disarming (and radical) idealism, which frames but also contrasts with the many brutalities of prison life it depicts, including the horrible assassination of Stiles (Richard Lawson). Once again in keeping with Mann’s later work, the rituals and vernaculars of the yard are precisely observed, and together form a compelling collective portrait of an ordinarily invisible community. Such authenticity, moreover, is no illusion; hundreds of actual inmates appeared as extras in the film, which was shot on-site in Folsom Prison. The running sequences, likewise, are fluently realised, and exhilarating to watch. In Rain’s last, solitary dash, it’s as if Mann and his cast of convicts have achieved a hard-won reply to the moral imperative W.H. Auden once articulated in a hopeless time: “In the prison of his days, / Teach the free man how to praise.”