- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

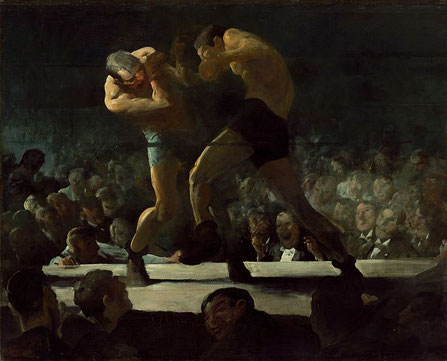

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

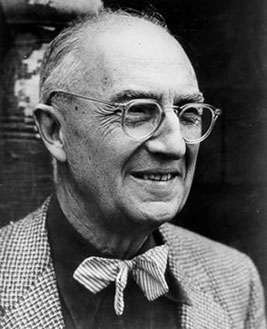

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

“I’m a radical! I write modern poetry, baby!”: William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

(A version of this essay was delivered as a paper at the William Carlos Williams Society's 2022 symposium, Challenging Williams)

INTRODUCTION

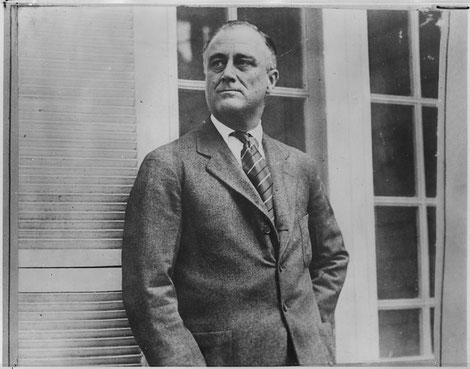

There has been a far-reaching discussion of Williams’s cultural politics in recent scholarship: ranging from his career-long association with anti-establishment magazines to the vivid depictions of poverty and illness found across his literary work, especially in his fiction. However, influential commentaries continue to cast Williams as more “pink” than red: a “small-d democrat” who approved of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal measures (in contrast to a number of his contemporaries), and a progressive whose experiences as a doctor-on-call heightened his sympathy for poor and working people. Williams’s refusal to join the Communist Party – and indeed, his sometimes fractious relationship with Party-affiliated journals – is cited as evidence of this view. The reading that follows builds on such analyses – particularly Cohen’s acknowledgement of Williams as “a genuine proletarian writer and sympathizer”, and Denning’s brief but insightful consideration of Williams’s “idiosyncratic” and “iconoclastic communism” – while also advancing a number of alternative propositions and interpretative inflections.

Tellingly, when questioned as to his political leanings in a late interview, Williams was unambiguous in his reply (if also suggestive in the rationale he provided): “I’m a radical!”, he exclaimed, “I write modern poetry, baby!” (I 20). Williams was unhesitant, and apparently cheerful, in categorising himself as a “radical”, and (in another interview) as “anticapitalistic” (I 78) – rather than a liberal, for instance, or a Democratic Party voter. And while researchers have acknowledged the combativeness and social consciousness of his short stories (and some of his essays and addresses), for Williams himself it seems to have been poetry that was the “social instrument” (SL 286), providing a means of registering and intervening in the cultural debates and political questions of his time. As he said elsewhere, one “can’t be a poet without knowing about interest and money. It’s not human to ignore people” (I 51): for him, economics and ethics, the political and the aesthetic, were in a continuous and quite natural state of cross-pollination. So this paper adopts and explores a paradigm that Williams himself proposed (however intermittently), in an effort to gain a clearer insight into the poetry he produced and the radical politics informing it.

WILLIAMS & THE NEW DEAL

As Paul Mariani notes, in April, 1945, when hearing of the death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR), Williams found himself “weeping for his lost leader”, the “man”, as far as he was concerned, “who had taken them through the Depression and seen them through the war”. Often referring to him as “the good President”, Williams had long been an admirer of the charismatic reformer, and on more than one occasion praised FDR himself, as well as the social and economic programme associated with him, in his work and letters. Perhaps fittingly, Williams responded to the news with the poem, “Death by Radio”. It reads:

Suddenly his virtues became universal

We felt the force of his mind

on all fronts, penetrant

to the core of our beings

Our ears struck us speechless

while shameless tears sprang to our eyes

through which we saw

all mankind weeping

(CP II 106)

Much of the poem’s phrasing is cumbersome or flat: “his virtues became universal”, “the force of his mind”, “the core of our beings”, and “Our ears struck us speechless” do little to evoke the intense understanding of FDR’s death they are supposed to convey. Certainly when compared to a work such as Whitman’s (likewise admiring) lament for Abraham Lincoln, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d”, Williams’s elegy seems somewhat slight – patriotically nostalgic and poetically hackneyed.

More suggestive for critical purposes is the poem’s (perhaps surprising) satisfaction to state the significance of FDR’s presidency and passing. “Death by Radio” has not discovered a universal truth so much as manufactured and exported it to all the globe, by sheer insistence: firm in the belief that the loss of FDR, along with the “virtues” of the politics he represented, is one for which the world itself should mourn. The poet is self-avowedly “shameless” in projecting his own “tears” and political emotion onto “all mankind” (CP II 106).

Williams had been slow to criticise FDR outright in his work. Now, he seems to have come close to adulating the “pseudo-aristocratic” yet egalitarian president in verse – an impulse arguably in keeping with the poet’s own longstanding reputation as “a forthright and unapologetic liberal”, who in common with many others had seen in FDR a stabilizing and humane influence “in a world that had become polarized between fascist reaction and socialist revolution”. Illuminating as such an interpretation can be, however, if embraced too fully it risks masking the limitations and failures of the New Deal as implemented over the course of FDR’s three-term presidency, as well as obscuring Williams’s consistent engagement with the deprivation and inequality that remained widespread across American society over the same period.

A decade after the stock market crash of 1929, and six years on from Roosevelt’s inauguration as President in 1933, Secretary of Commerce Harry Hopkins could remark that with “12 millions unemployed, we are socially bankrupt and politically unstable.” As Howard Zinn retrospectively observed:

When the New Deal was over, capitalism remained intact. The rich still controlled the nation’s wealth, as well as its laws, courts, police, newspapers, churches, colleges. Enough help had been given to enough people to make Roosevelt a hero to millions, but the same system that had brought depression and crisis – the system of waste, of inequality, of concern for profit over human need, remained.

As hinted above, if Roosevelt remained a hero of Williams’s (and primarily for the reasons Zinn suggests), the poetry nevertheless bore testament to the “waste”, “inequality” and neglect of basic human needs seemingly built into America’s economic and political life. Williams’s poem, “Election Day”, thus reads as follows:

Warm sun, quiet air

an old man sits

in the doorway of

a broken house –

boards for windows

plaster falling

from between the stones

and strokes the head

of a spotted dog

(CP II 25-6)

The piece extends an internal tradition in Williams’s work, wherein the descriptive poem assumes parabolic resonance through its very literalness and individuation (a list of similar items from Williams’s corpus might include “Proletarian Portrait”, as well as some less obviously political snapshots of daily life, like “The Great Figure” or indeed “The Red Wheelbarrow”). “Election Day” functions as a kind of kinetic palimpsest – the gradual encroachment of social neglect, the “boards for windows / plaster falling”, underlaying the man’s own physical presence and process, as he “strokes the head” of his (possibly ill) dog. The title, of course, freights these immediacies with political meaning – linking the situation described to the organisation and electoral traditions of American society as such. In its way, the old man’s “broken house” may reflect (possibly even accuse directly) the greater house of American democracy, divided or otherwise.

“Election Day” can also be seen to contain an inside joke, whereby Williams wags the dog (in this case, a literal “spotted dog”), as if to distract attention away from the political and social implications of the scene described. The result – quite intentionally on Williams’s part – is the opposite. By virtue of its very marginality, the slow, permeating poverty of the old man’s surroundings stands in a metonymic relation to American society as a whole.

In the broadest sense, Williams is also highlighting the material conditions which even the most seemingly self-enclosed of poetic images “depends / upon” (CP I 224). As he wrote to Kenneth Burke in the late 1940s, “[m]y whole intent, in my life, has been [to] find a basis (in poetry, in my case) for the actual” (SL 257). Or as he memorably asserted elsewhere: to “speak, / euphemistically, of the anti-poetic” is “Garbage”, for it leaves “[h]alf the world ignored” – a circumstance he seemed intent on rectifying here (CP II 68). “A Portrait of the Times” is similarly rooted in a late 1930s New Jersey town. “Two W. P. A. Men”, the poem notes,

stood in the new

sluiceway

overlooking

the river –

One was pissing

while the other

showed

by his red

jagged face the

immemorial tragedy

of lack-love

while an old

squint-eyed woman

in a black

dress

and clutching

a bunch of

late chrysanthemums

to her fatted

bosoms

turned her back

on them

at the corner

(CP II 9-10)

The mosaic-like snapshot of the two men and the wincing woman ironises the installation of a local drainage system, in light (once again) of its human process. Importantly, the representativeness of the poem’s situation – that which makes it “A Portrait of the Times” – stems primarily from the fact that the men are employed by the “W. P. A.”, or the Works Progress Administration: one among a number of far-reaching New Deal programmes providing paid work to exactly that class of citizens whose privations Williams portrayed so often and so vividly in his work, early and late. As we’ve seen, the actual success of the W. P. A. in generating economic prosperity and alleviating social hardships has been questioned by a number of historians and political commentators. In William Appleman Williams’s view:

The New Deal saved the system. It did not change it... the main efforts of relief, rationalization, and reform actually occurred in a jumble rather than proceeding in any step-by-step order or neat plan of development. Pragmatic to the core, the New Deal was not so much misdirected as it was undirected.

One result being the social bankruptcy and soaring levels of unemployment identified by Harry Hopkins in 1941.

Significantly, Williams’s poem contemporaneously casts the effectiveness of the W. P. A. scheme in doubt, with its focus on the slapstick element of the labour involved, as well as on the “jagged” and “immemorial tragedy” of the worker’s face – a guarded, but perspicacious retort to the supposed progress signalled by the Roosevelt administration’s labour reforms. In this respect, the piece merits comparison with Robert Frost’s famous (and famously critical) New Deal-era poem, “Two Tramps in Mud Time” (1934). In the latter, the Frost-persona questions whether he should offer his wood-chopping work to two men who had been “sleeping God knows where last night, / But not long since in the lumber camps” – and ultimately rules against such a course of action, declaring that although “I had no right to play / With what was another man’s work for gain”, his own situation, in which “love and need are one”, grants him more of a moral claim to the labour than the “two hulking tramps”. Artful as it is, the poem in effect gives literary life to Frost’s complaint at the time, that “the lower classes” are now “to be completely taken care of by the upper classes”, as he wrote in 1939. Or as George Monteiro notes, “Two Tramps” records Frost’s skepticism towards “the basic premise of practicing social welfare”, particularly when this comes at the supposed detriment “of an individual’s right to well-being” – Frost’s meditation on physical (and personal) labour in a time of general poverty founded on a dichotomy of “the needs of spirit, aspiration, and self-fulfillment against the need for working for food.”

Frosts’s rankled opposition to “working for food” may of course help to contextualise Williams’s view of the older poet “as a reactionary with ’no grasp of the crucial issues’ facing his world”, particularly compared to Williams himself, with his sensitivity to questions (and “the facts”) of deprivation throughout his life. In any case, Frost’s poem in turn clarifies Williams’s approach in “A Portrait of the Times”, which draws into its critical spotlight not social welfare as such, but the effectiveness of those programmes already implemented – as well as the physical wellbeing, the embodied humanity, of the various actors described. Frost was mounting an ethical critique of the very idea of social welfare; Williams was attempting to replace a myth of national progress with a picture of the New Deal as it actually existed in the lives of ordinary Americans.

It’s also worth noting the remarkable extent to which the poem’s political commentary is an effect of its exploratory visual practice – standing as another of Williams’s emblematic, if precisely observed social documents. Williams’s portrait seems almost obsessed with forms of seeing and impediments to sight – both internal to the scene described and relating to Williams’s own creative-spectatorial role. The two men are “overlooking / the river”, although in opposite directions: one, towards the water into which he is “pissing”, and the other, presumably, towards Williams himself, who consequently can study his face with such clarity. The old woman, similarly, is “squint-eyed” and actively reluctant to observe the scene, turning her back on the W. P. A. workers “at the corner” (CP II 10). Williams’s own role, finally, is all-seeing and artistically integral, and yet seems curiously constrained, lacking (in this instance) the motion and agency which the other figures clearly possess.

The poem is a noticeably unheroic – and yet, for Williams, typically street-rooted – depiction of how the Works Progress Administration schemes were actually administered. For all the self-aggrandizing rhetoric of a nation renewed, in the New Deal years the “jagged” reality of social life, or what Williams elsewhere termed “the sharp edge of the mechanics of living” (SE, 237), had persisted and intensified, leaving many of America’s “old” and “squint-eyed” citizens atomised, burdened by “lack-love”, merely passing (or “pissing” away) what time they had or the little work they could find. Williams, as was his wont, recorded the spectacle – in a manner akin to Pieter Brueghel the Elder, whom he portrayed much later (in his final collection of poems) as an “alert mind dissatisfied with / what it is asked to / and cannot do”, who nonetheless “accepted the story and painted / it in the brilliant / colors of the chronicler” (CP II 387).

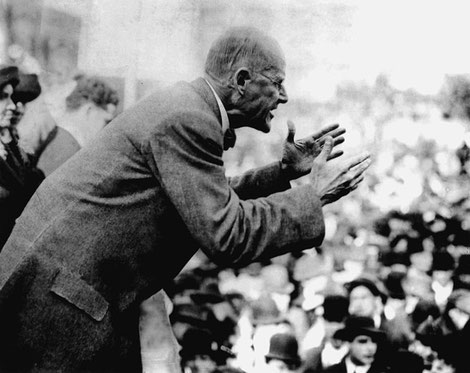

WILLIAMS ON THE LEFT

It should be remembered that FDR was not the only (nor even the foremost) contemporaneous political figure whom Williams admired. This comes clear in an interview given at the tail-end of the New Deal years. When asked, “What do you think the responsibilities of writers in general are if war [i.e. World War II] comes?”, Williams replied not by praising the then-president, but by outlining a position that managed to be both forthright and nuanced. “If war comes we’ve got to fight”, he said, in a declaration consistent with his own anti-fascist orientation throughout the 1930s (and indeed with the ideals of other left-wing poets, including Langston Hughes, who combined a sharply critical analysis of American society with a visceral understanding of the necessity of defeating Europe’s fascist powers). “Meanwhile”, Williams added, “long live in America the memory of Eugene Debs” (I 80)– referring to the perennial Socialist Party presidential candidate, who contested elections on the party ticket in 1904, 1908, 1912 and 1920. Famed for his passionate critiques of social inequality, Debs, who died in 1926, had been imprisoned for his opposition to America’s entry into the First World War. During the latter episode, in 1918, he famously declared: “while there is a lower class, I am in it, and while there is a criminal element, I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.”

For a poet frequently criticised for his waywardness and simplifications, Williams’s abiding respect for Debs arguably indicates something of the subtlety (and, of course, the radicalism) of his cultural understandings. Debs’s pacifism remained instructive, in Williams’s view, even (or especially) with another global war looming. And like Debs, as we know, Williams was unshakeably sympathetic to America’s “lower class” of workers and vagrants: people worn down by labour or shut out by society. “Why do I write today?”, Williams had rhetoricised in his early years: the “beauty of / the terrible faces / of our nonentities / stirs me to it” (CP I 70). As with Debs, moreover, this identification on Williams’s part extended to those persecuted as criminals. As he wrote of the convicted radical John Coffey in 1935: “Let him be / a factory whistle”

That keeps blaring –

Sense, sense, sense!

So long as there’s

a mind to remember

and a voice to

carry it on –

(CP I 378)

Referring to the activist’s decision “to steal goods from department stores” in order “to help the poor” (an action for which he was incarcerated), Williams also defended Coffey in an article published in The Freeman in June 1920, claiming that “[w]hat Coffey was after was definition, a light in the dark, a diagnosis, without which no advance of knowledge is possible” (CP I 536-537) – a summary that arguably speaks as much to Williams’s own concerns in this period as to Coffey’s motivations.

The same may be said of Williams’s unrestrained condemnation of judge, jury, and general public in wake of the Sacco and Vanzetti case, in 1927. “Americans”, his poem reads, “You are inheritors of a great / tradition”, despite doing only “what you're told to do. You don't / answer back the way Tommy Jeff did or Ben / Frank [...] You're civilized” (CP I 272). The logic here is telling. For if Williams’s urge as a poet was to “answer back” to his times, then such an impulsion, in his view, was almost by definition an American one: to be both dissident and dissonant amid the prevailing orthodoxies of the time, like “Tommy Jeff” or “Ben / Frank” (amusingly re-cast by Williams almost as neighbourhood mates, “Tommy” and “Ben”, rather than two of the U.S.A.’s founding elites) – or like Sacco and Vanzetti themselves.

Railing against the “arbitrary statutes” and “pimps to tradition” allegedly governing American society, the poem highlights what Williams viewed as the bias and malfeasance of this juridicial caste, perpetrating butchery “for the glory of the state / and the perpetuation of abstract justice”, and all “in the face of the facts” (CP I 270-271). “No one / can understand what makes the present age / what it is”, Williams concluded, so long as they remain “mystified by certain / insistences” (CP I 272), a condition the poem sets out to remedy, demystifying the power dynamics at play in the trial, and also affirming, in the most consequential manner, Williams’s later adage that there could be “[n]o ideas but / in the facts” (P 27).

In some respects, Paterson may also be read as a complex exercise in exactly this kind of class-conscious, cultural demystification – with the proviso that it is Williams’s esoteric (and sometimes vexed) understanding of class relations that prevails, rather than the dialectics of Marxist thought per se. “I am not a Marxian”, Williams famously declared to Babette Deutsch (SL 259).

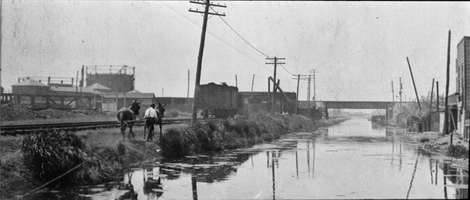

One of the most significant elements of Paterson’s progression, however, is the frequency with which the “interpenetration, both ways” of past and present that Paterson posits is framed in terms of the local area’s legacy of labour struggle. By the turn of the twentieth century, the city had become a hotbed of anarchist activity, its working-class communities giving shelter to the legendary agitator, Errico Malatesta, escaped from an Italian prison with the aid of an international network of underground organisers. Within a decade, Paterson was synonymous with industrial unrest. “Rose and I didn’t know each other when we both went to the Paterson strike”, one prose interpellation reads:

She went regularly to feed Jack Reed in jail and I listened to Big Bill Haywood, Gurley Flynn and the rest of the big hearts and helping hands in Union Hall. And look at the damned thing now.

(P 99)

In Williams’s rendering, the city and its denizens remain marked by the memory of a politics – a tradition of mutual aid and civic solidarity – that was once, and might have been for longer, had the hopes of “Big Bill Haywood” and Elizabeth “Gurley Flynn” been realised, and the movement of “big hearts and helping hands” they represented been allowed to flourish. The poem’s specific observation in this instance is that “now”, by contrast, Paterson seems “damned”, in the long aftermath of the defeat of the silk mill-workers’ strike of 1913. The extract also particularises the project and intentions of Paterson’s narrator, who, we are told,

[...] dozes in a fever heat, cheeks burning . . loaning blood to the past, amazed . risking life. And as his mind fades, joining the others, he seeks to bring it back –

(P 101)

Conscious of the decayed state of Paterson in the present, Williams’s persona attempts to give imaginative life (and indeed, to bear witness) to the past – including, once again, to that history of radical and subversive solidarity now lacking in the city’s social life (P 99). Paterson reiterates this position and extends its critical reach later, with a recollection of the preacher, “Billy Sunday evangel”, in 1915 – his high-flying oratory intended to divert the crowd of strikers towards religion, and away from further industrial revolt:

He’s on the table now! Both feet, singing (a foot song) his feet canonized . . as paid for by the United Factory Owners’ Ass’n . . to “break” the strike and put those S.O.Bs in their places, be Geezus, by calling them to God!

(P 172)

For all of Williams’s stated distrust of Marxist thought, Paterson’s portrayal of social relations is reminiscent of the German philosopher’s own – specifically, in its critique of organised religion. Just as Marx depicted religion as “opium for the masses”, deflecting the fervour of revolutionary activity into a cult of personal salvation, so Paterson observes the city’s working classes as forced, by their situation, into a debilitating combination of spiritual hope and political inertia: “these poor souls”, the poem reads, “had nothing else in the world, save that church, between them and the eternal stony, ungrateful and unpromising dirt they lived by” (P 62). For Williams, as for Marx before him, religion was often the only “heart” in the “heartless world” his people inhabited, and “the unpromising dirt they lived by” the ground in which his own art would flourish.

THE AFFILIATED WILLIAMS: A NOTE

As in his identification with Debs, Coffey, and the IWW above, on many occasions throughout his life Williams found himself positioned to the left of America’s Communist Party (CP). His views, often encoded into his poetry, chimed with socialist and anarchist critiques of that institution, indeed, even as he recognised the urgent need for what he called the “equalisation of wealth between the rich and poor” in American society, and farther afield (ARI 184). “I wasn’t a Communist”, he stated, “but I was anticapitalistic” (I 78).

As late as 1948, Williams could be found arguing that “there is much justice in the insistency by Communism upon a literature based upon a people’s good”, while observing, pointedly, that in “order to serve the cause of the proletariat”, the writer “must not under any circumstances debase his art to any purpose” (ARI 75). As Douglas Wixon remarks, Williams was “[w]arm to the aims of the Communist party regarding social justice”, even as he “distrusted the party’s covert functioning and dogmatic pronouncements.”

In this regard, Williams’s well-documented praise for the sharecropper bard, H. H. Lewis, is revealing. Acknowledging the poet’s political affiliations as integral to the nature and perspective of the work he produced, Williams nevertheless re-frames the political positionality of the poems, presenting Lewis, in his gutsy non-conformism, as an inheritor of a quintessentially American tradition. “There is a lock, stock, and barrel identity”, Williams asserted,

between Lewis today, fighting to free himself from a class enslavement which torments his body with lice and cow dung, and the persecuted colonist of early American tradition. It doesn’t matter that Lewis comes out openly, passionately, for Russia. When he speaks of Russia, it is precisely then that he is most American....

(SS 77)

Williams valued, and seems to have identified emotionally with, the rebellion and class anger permeating Lewis’s work; he accepted and understood the latter’s fervent embrace of the CP as another expression of these impulses, but did so (crucially) without following him.

Far from confirming Williams as a liberal at heart, however, his hesitancy in joining Lewis and others as members of the CP is arguably indicative of the combination of libertarianism (stressing individual freedom and autonomy) and socialism (the capacity for communal feeling and active solidarity) informing his outlook. In his definitive History of Marxism in America, Paul Buhle expresses similar reservations about the CP in hindsight. In the USA, he writes,

Marxist doctrine in its internationalist abstraction has run up against a vast tide of complex group loyalties and vernaculars... [which] could appeal beyond the limits of class and ethnicity-bound Marxism, beyond homo economus, to a recurrently troubled national conscience and democratic discourse that [party] theoreticians failed to comprehend.

For Williams, likewise (and once again), there could be “[n]o ideas but / in the facts” (P 27).

Critics, in brief, should not allow this proclaimed hostility to Marxist dogma, and the actualities of the Stalinist project, to obscure Williams’s abiding and politically incendiary sense of common cause with labourers and radicals – in Russia and America alike. “Wherein is Moscow’s dignity / more than Passaic’s dignity?”, Williams wondered in “The Men”,

The river is the same

the bridges are the same

there is the same to be discovered

of the sun –

(CP I 278)

Williams’s radicalism was homegrown but with an internationalist dimension, infused with human sympathy and instinctive comaraderie, and remained rooted in the specificities of life and labour as these were actually experienced on the ground. This combination of elements, moreover, allowed him to document the inequalities of American society, and to acknowledge the struggles of living communities (which included dissidents and labour organisers), but, significantly, without succumbing to the schematism and dubious moral posturing of contemporaneous, party-oriented forms of anti-capitalist agitation. “A labor revolution by a society seeking to be in fact classless”, as Williams declared to a gathering of Social Credit reformers in 1936 (considerably radicalising the scope and message of the convention), “is both great and traditionally American in its appeal” (SL 115).

Williams’s enthusiasm for the Social Credit movement, and his relationship with Ezra Pound, can itself be understood within this broader political paradigm. This is an important point, as scholars within and adjacent to Williams Studies have tended to interpret such affiliations as proof of an at best confused commitment to left-wing politics. In The Poets of Rapallo, Lauren Arrington takes Pound’s association with the Social Credit movement as evidence in itself of his antisemtitic leanings, and, vice versa, of the movement’s own reactionary content and orientation. Arrington’s focus is on Pound and his immediate circle in Italy during the inter-war years, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that Williams is only mentioned in passing; and yet the work and example of Williams, who was also a willing pamphleteer for Social Credit, go against the grain of Arrington’s thesis in important respects.

In some quarters, Williams’s politically engaged conception of poetry has been presented almost as an effect of his longstanding friendship with Pound, both poets forging and enacting a “Jeffersonian” critique of America’s political and economic system in their respective works. As Alec Marsh notes, both writers “were engaged in what we would now call ’cultural criticism’”, a criticism that “extends to their poetry and into the poems themselves”, which set out to measure “the true ideal of democracy” against “the false ideal of success, especially commercial and monetary triumph” that each perceives as an active force in American society.

In fact, while Williams shared with Pound (and to some extent may have inherited from him, in his early years) an active and politically excursive conception of literary purpose, the content and direction of his poetic endeavours were distinct from his friend’s in a number of crucial respects. As far back as their student days, “around 1905”, Williams recalled,

I used to argue with Pound. I’d say ‘bread’ and he’d say ‘caviar’ [....] Once, in 1912 I think it was, in a letter (we were still carrying on our argument) he wrote, ‘all right, bread.’ But I guess he went back to caviar.

(I 81)

Likewise, while Pound’s perception of the “filthy, sturdy unkillable infants of the very poor”, who some day will “inherit the earth”, blends irony and disdain, Williams’s gut-rooted urge to “walk back streets / admiring the houses / of the very poor (CP I 64) genuinely exults in the rough-and-tumble vitality of the same. “It’s the anarchy of poverty / delights me”, he declared (CP I 204).

Perhaps more pertinently, where Pound mixed credit reform with racism and strong-man polemics, Williams was consistently anti-fascist in his declarations and endeavours. In 1939, expressing his contempt for “that murderous gang [Pound] says he’s for” (referring to the fascist parties of Hitler and Mussolini in Europe), Williams confessed to James Laughlin that he could “hardly bear the thought of shaking hands with the guy if he does show up here – I’d say the same to my own father under the circumstances ”, adding later:

The logicallity [sic] of fascist rationalizations is soon going to kill him. You can’t argue away wanton slaughter of innocent women and children by the neo-scholasticism of a controlled economy program.

(JL / WCW 45-49)

In addition to such privately expressed sentiments, Williams penned an open criticism of Pound in 1941, published as “Ezra Pound: Lord Ga-Ga!” – described succinctly by Paul Mariani as a “palpable hit at the man who had set himself up as an insane Lord Haw Haw”. As Williams asserted elsewhere of Pound’s “totalitarianism”: “I disagree with him fundamentally and finally in what I believe he, as a man of responsibility, represents.”

There are also clear formal differences between the two. It would be misleading, for example, to interpret the Paterson project – arguably Williams’s most “Jeffersonian” (or at least, anti-Hamiltonian) of works – as an attempt to write a poem including history, to adapt Pound’s definition of The Cantos. The poem, after all, does not merely incorporate the fact of Hamilton’s influence on the Paterson area, but uses the epic mode to critique what Williams called in his Autobiography the “fiscal colonial policy” and elitism of Hamilton as a figure (A 391). Pacing among the detritus and apparently toxic atmosphere of the Passic riverbanks, Paterson’s self-assigned mission is to draw up from the wasted products of Hamilton’s vision – from the polluted falls to the “[t]enement windows, sharp edged, in which / no face is seen” (P 37) – a serviceable and accurate imagination of American life. As Angela Hume notes in another context, “readers find themselves well outside the realm of nature poetry, instead approaching something more akin to a poetics of environmental justice”, one that rejects “the sublime wilderness ideal” in favour of America’s blasted “landscapes, along with the people who inhabit them”. Moreover, it is these people, very often, who ground and direct the crowded, clamouring, aspirational democracy of Paterson as a work, in contrast to The Cantos, which remains tethered throughout to Pound’s own eclectic (and sometimes reactionary) interests.

“The wealthy / I defied”, Williams wrote in one late poem: the wealthy and those “who take their cues from them” (CP II 321). For “the poor” of Rutherford, he recalled by contrast, “I was deeply sympathetic and filled with admiration” (as Pound was not): “I would have done anything for them, anything but treat them for nothing, and I guess I did that too” (IWWP 49-50).“I never tire of the mystery / of these streets”, he wrote, where “flags in the heavy / air move against a leaden / ground” (CP II 108-9) – recasting the patriotic symbols of American nationhood in terms of the “the factory, the dirty / snow” known by the working poor, the snow “trampled and lined with use” (CP II 109). For Williams the radical, people came first; so his instinct, commendably, was to resist the (sometimes murderous) “neo-scholasticism” to be found among the dissidents and anti-establishmentarian milieux that attracted other poets, on both Left and Right.

WILLIAMS & THE COMMONS

In recent years, among certain sections of the post-Marxist Left, there has been a turn away from doctrinally framed histories and activist programmes, and towards a renewed investigation of “the commons” – of mutual aid, the ecology of co-operation, and communality as such – as a form of radical potentiality, particularly in the age of climate crisis. Marcus Rediker describes this critical approach simply as “the poetics of history from below”, while Kevin B. Anderson adopts the same paradigm as a means of revitalising Marxist historiography itself in light of the philosopher’s own interest, late in life, in a variety of indigenous and so-called primitive modes of collective organisation, ranging from tribal customs in Algeria to peasant communes in rural Russia.

Writing with a view to challenging the “concerted neoliberal drive to privatize the remaining communal and public resources”, Silvia Federici develops this framework further by highlighting the role of women’s labour in working-class history, as well as the diverse practices of “commoning” that have sustained peasant, indigenous, and proletarian cultures across a range of modern and early modern contexts. Attempting to address what she calls “the most vexed question of capitalist development: who owns the land?”, Federici argues that first the word

community has to be [understood] not as a gated reality, a grouping of people joined by exclusive interests separating them from others... but rather as a quality of relations, a principle of co-operation, and of the responsibility to each other and to the earth, the forests, the seas.

If “commoning has any meaning”, she writes, “it must be the production of ourselves as a common subject... no commons without community”. Peter Linebaugh reaches a similar conclusion in his field of research – focused on the “revolutionary Atlantic” – pointing out (against the prescriptions of traditional Marxist historiography) that “commonism preceded capitalism on the North American continent, not feudalism”. As is also true of Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, among others, Linebaugh draws attention to the fact that indigenous American societies have been continuously “resisting the commodification [of] Mother Earth as real estate” since at least the fifteenth century. For Linebaugh, “the commons means equality of economic conditions”, and so, as a term and political model, “suggests alternatives to patriarchy, to private property, to capitalism, and to competition”.

What unites these analyses is their foregrounding of the shared customs, common spaces, communal practices, and self-activity of actual people, often living on the so-called margins of industrial or imperial development. Unlike previous Communist historians in the West, moreover, this scholarship acknowledges such zones and modes of experience as inherently radical: productive, that is, of salutary and potentially revolutionary forms of consciousness and community. As the final section of this paper will attempt to show, to an unusual degree Williams’s poems register, affirm, and anticipate “the commons” as understood in this emerging school of inquiry (understood, in other words, as a set of discernible material practices and customs, and as a radical paradigm of anti-capitalist thought and politics).

~

Williams’s work pulses with the intuition that “To Be Hungry Is To Be Great”. Indeed, his poem of that title combines ecological attentiveness with rowdy proletarian hope in its celebration of the “yellow grass-onion, / spring’s first green, precursor / to Manhattan’s pavement” (CP I 400). Even in America’s sprawling cities, Williams proposed, the Spring’s returning “green”, the onion, might be “plucked”, “washed, split and fried”, then “served hot on rye bread [...] to beer a perfect appetizer.” And “the best part / of it”, he concluded, “is they grow everywhere.” As Linebaugh summarises (albeit not in relation to Williams’s poem specifically): “Enclosure is never absolute: there are always means of getting under, over, through, or around”. And as he insists elsewhere: the “commons are renewed and class solidarity is maintained” through the pleasure of shared sustenance, “starting in the kitchen”.

In a similar manner, “To a Poor Old Woman” – along with “This Is Just to Say”, arguably Williams’s most famous poem of hunger (and plums) – holds against the visual evidence of the woman’s poverty the equally palpable fact of the pleasure she gains, the “solace” she draws, from “munching a plum on / the street”, transforming what might have been a portrait of destitution into an open-air spectacle of ease and unabashedness: “They taste good to her / They taste good / to her. They taste / good to her” (CP I 383). Williams had an uncanny ability to look at hunger, and perceive humanity; to register the wreckage and pollution of industrial modernity, and yet to sense the changing seasons, the renewal of the natural world beneath the surface.

“A Poem for Norman MacLeod” (perhaps lightly chiding the dogmatism of his young Communist correspondent) encompasses each of these concerns, declaring that the “revolution” will be “accomplished” when “noble has been / changed to no bull” (CP I 401). “You can do lots / if you know / what’s around you”, Williams winks,

Or as Chief

One Horn said to

the constipated

prospector:

You big fool!

And with his knife

gashed a balsam

standing nearby

Gathering the

gum that oozed out

in a tin spoon

it did the trick

(CP I 401)

The poem is typical of Williams’s work and world-view in the punful delight it takes in acknowledging the teeming, scatological vitality of American life. And it chimes with (enacting in the most literal and down-to-earth way possible) José Carlos Mariátegui’s memorable assertion, that “[t]he indigenous reality will reveal the shining path to socialism”. Likewise, the exuberant reference, laden with innuendo, to “Chief / One Horn” is illuminating, partly as a signal of Williams’s democratic instincts, but also for what it tells us about his sense of place and history. Indeed, to an unusual degree – certainly when compared to many of his immediate contemporaries – Williams was alive (and sympathetic) to indigenous experiences (as discussed here).

If Williams was capable of folding a critique of what Frederic Jameson (in his reading of Paterson) calls “domination and imperialism” into his descriptive verse, his almost photographic miscellany of everyday American sights and scenes also serves, very often, to expose and question the structures of ownership, social division, and wealth disparity that frame social life in the USA. In one poem, Williams’s sparse, apparently undemonstrative portrayal of a “sewing machine / whirling // in the next room” comes to emblematise both the financial want and the practical industriousness of an entire household – as nearby the “men at the bar” are “talking of the strike / and cash” (CP I 299).

Similarly in his piece, “Morning”, Williams manages to delineate a complex system of property rights and contrasting entitlements by the mere cataloguing of incidental details, perceived in an ostensibly humdrum locale. The poem envisions a line of “truncated poplars / that having served for shade / served also later for fire” (CP I 459-60), before tracing the social contours of the surrounding area:

Down-hill

in the small, separate (Keep out

you) bare fruit trees and among tangled

cords of unpruned grapevines low houses

showered by unobstructed light.

(CP I 459-60)

The friction between the sunlit, seemingly “unobstructed” tranquility of the scene and the system of legalistic divisions underlying it injects a compulsive energy into Williams’s lines here: “(Keep out / you)” a social imperative the poem uncovers, and partly derides. Once again, Williams in his stance and attitude diverges from a number of his contemporaries, not least Wallace Stevens – whose sense of poetry’s public situation is concerned, as Joseph Harrington tactfully summarises, “less [with] the right to free speech than with the much older rights to privacy and to property and with the separation of spheres that undergirds those rights”: a “separation of spheres” that Williams, as we have seen, recognises as real and seeks (playfully) to up-end.

In its dissection of the rules and significance of private property in America, “Morning” may serve as both echo and antiphon to Williams’s “Portrait of a Woman in Bed”, published twenty years beforehand. In the earlier poem, the titular character mounts a concise rebuttal to the reverence for private ownership, as well as the persistent moralism, to be found among middle-class society. “I won’t work / and I’ve got no cash”, the woman snaps, “What are you going to do / about it?” –

This house is empty

isn’t it?

Then it’s mine

because I need it.

Oh, I won’t starve

while there’s the Bible

to make them feed me.

(CP I 87-88)

As Paul Cappucci summarises: “[n]ot only does she refuse to work and make money, she issues a challenge to the landlord [and] claims possession of the house”.

Williams’s apparently effortless marriage of material consciousness and idiomatic speech above is of course representative of the democratic (and again, radical) perspective and emphasis of his work. The poem’s tone is also instructive, in every sense: the line-breaks interweaving the old woman’s conviction with the listener’s anticipated delight at the force and fluency of her self-expression. The line, “it’s mine / because I need it”, is scintillating as argument, but all the moreso for the plainness of its articulation and the clarity of its appearance on the page.

As in Federici’s analyses, there is also a gendered edge to Williams’s critique of private property here. The poem delights not just in the efficient dismantling of social hypocrisies, but also in the fact that it is an old woman who has effected the change in perspective. In Williams’s early “The Young Housewife”, the central figure is constricted and yet made mysterious by the visual veil of “her husband’s house” (CP I 57). Here, however, the poet is deferential and attentive to the woman and her self-assigned enitlements – to property, that is, and to speech. “[Y]ou / can go to hell”, she quips:

You could have closed the door

when you came in;

do it when you go out.

I’m tired.

(CP I 88)

The poem’s plainspokenness marks a double achievement: that of realising a recognisably American idiom on the page, but also of revising social (including Williams’s own) assumptions of private right and poetic articulacy. The woman herself has the last word, and the house consequently remains – or perhaps becomes – her own.

CODA

If Williams followed a sometimes erratic trajectory of affiliation with leftist and anti-establishment movements, journals, and political figures, his sympathies nevertheless gravitated towards the far-left of the political spectrum. He valued the example and identified with the struggles of the Socialist Party, the IWW, and indeed the living (often downtrodden and even criminalised) communities he encountered on his medical rounds. Whatever “communism” (“idiosyncratic” or otherwise) Williams cleaved to in his life and work should be understood in these contexts, rather than measured in terms set by the Stalinist party committee, the Trotskyist editorial board, or his fellow travellers in the Social Credit movement (with whom Williams self-consciously maintained a number of important political differences).

Williams’s poems, moroever, have proven radical and prophetic: grounded in the material specificities of their place and moment, even as they anticipate in outline the new paradigms of democratic (and ecological) imagining that are slowly replacing the dogmas and orthodoxies of conventional Leftist thought. Williams documented the social strains and personal vitalities of the New Jersey streets he knew, from an eye-level, grassroots perspective, and in the process formulated a sympathetic, deep-delving vision of “the commons”, which he viewed as part of the fabric of daily life in America. For him, as for scholars and activists since, this was a space of co-operation and recognition, of interaction and mutuality, created and sustained by people themselves: where the weary can speak, where the sick are housed according to their “need”, where indigenous humour and customs can be revived, and where, even in the stark metropolis, a flush of plums, the flourishing fruits of spring, can be discovered anew, giving pleasure to the poor and “solace” to the hungry. Without shirking the often brutal inequalities and exploitations of industrial modernity, Williams’s radicalism returns us to the world and to one another, lit by the simple but inspiring belief that “you can do lots / if you know / what’s around you”. No bull.

Ciarán O'ROurke // June 2022

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary

ARI Williams, William Carlos, Dijkstra, Bram, ed., A Recognizable Image: WCW on Art and Artists (New York, 1978).

CP I — : Litz, Walton A., MacGowan, Christopher, eds., Collected Poems I: 1909-1939 (New York, 2000/1991).

CP II — : MacGowan, Christopher, ed., Collected Poems II: 1939-1962 (New York, 2000/1991).

I — : Wagner, Linda, ed., Interviews with William Carlos Williams (New York, 1976).

IAG — : In the American Grain (New York, 1966/1925).

IWWP — : Heal, Edith, ed., I Wanted to Write a Poem (New York, 1976/1958).

P — : MacGowan, ed., Paterson (New York, 1995/1992).

SE — : Selected Essays (New York, 1969/1954).

SL — : Thirlwall, John C., ed., Selected Letters (New York, 1957)

SS — : Breslin, James E., ed., Something to Say: William Carlos Williams on Younger Poets (New York, 1985).

WCW / JL — : Wintemeyer, Hugh, ed., William Carlos Williams & James Laughlin: Selected Letters (New York, 1989).

Secondary

Anderson, Kevin B., Marx at the Margins: On Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western Societies (Chicago, 2010).

Buhle, Paul, Marxism in the United States: A History of the American Left (New York, 1987/2013).

Capucci, “’And Everyone and I Stopped Breathing’: William Carlos Williams, Frank O’Hara, and the News of the Day in Verse”, Papers on Language, Vol. 39 Issue 4 (Fall, 2003).

Cohen, Milton A.,“Stumbling into the Crossfire: William Carlos Williams, Partisan Review and the Left in the 1930s”, Journal of Modern Literature, Vol. 32 Issue 2 (Winter, 2009).

Davis, Mike, Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the US Working Class (New York, 1986/2019).

Denning, Michael, The Cultural Front (London, 1996).

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne, An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States (Boston, 2014).

— : Outlaw Woman (Oklahoma, 2014).

Faggen, Robert, The Cambridge Companion to Robert Frost (Cambridge, 2001).

Federici, Silvia, Re-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons (San Francisco, 2018).

Frost, Robert, eds., Poirier, Richard, Richardson, Mark, Collected Poems, Prose and Plays (New York, 1995).

Harrington, Joseph, Poetry and the Public: The Social Form of Modern U.S. Poetics (Middletown, 2001).

hooks, bell, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (New York, 1994).

Hume, Angela, “Toward an Antiracist Ecopoetics: Waste and Wasting in the Poetry of Claudia Rankine”, Contemporary Literature, Vol. 57 No. 1 (Spring 2016).

Jameson, Frederic, The Modernist Papers (London, 2007).

Klein, Naomi, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate (New York, 2014).

Kornbluh, Joyce L., ed., Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology (London, 2011).

Linebaugh, Peter, Stop, Thief!: The Commons, Enclosures, and Resistance (San Francisco, 2014).

— : Red Round Globe Hot Burning (Oakland, 2019).

MacGowan, Christopher, ed., Cambridge Companion to William Carlos Williams (Cambridge, 2016).

Mariani, Paul, William Carlos Williams: A New World Naked (San Antonio, 1981).

Marsh, Alec, Money and Modernity: Pound, Williams, and the Spirit of Jefferson (Tuscaloosa, 1998).

McRae, Calista, “Williams, Thom Gunn, and Humane Attention”, William Carlos Williams Review, Volume 34 No. 1 (Spring, 2017).

Miller, Joshua L., Accented America: The Cultural Politics of Multilingual America (Oxford, 2011).

Pells, Robert, Radical Visions and American Dreams: Culture and Social Thought in the Depression Years (Toronto, 1973/1998).

Pound, Ezra, Personae (London, 1926/2001).

Turcato, David, ed., The Method of Freedom: An Errico Malatesta Reader (Chico, 2014).

Von Hallberg, Robert, “The Politics of Description: William Carlos Williams in the Thirties”, ELH, Vol 45, No 1 (Spring, 1978).

Williams, William Appleman, The Contours of American History (New York, 1961).

Wixson, Douglas, “In Search of the Low-Down Americano: H. H. Lewis, William Carlos Williams, and the Politics of Literary Reception, 1930-1950”, Williams Carlos Williams Review, Vol 26, No1 (Spring, 2006).

Zinn, Howard, A People’s History of the United States (New York, 1980/2003).