- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

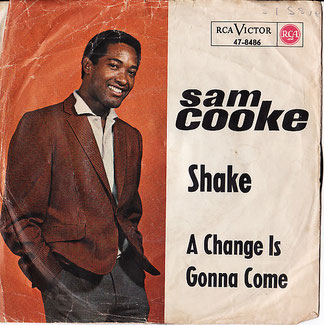

Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

(First published by Hard Crackers)

It’s a truism, but nevertheless may be worth repeating: that music and literature of a radical bent can encapsulate the possibilities of their social moment in a way that manifestos and movement histories, no matter how subversive their authors’ politics, are sometimes just unable to match. Yesterday’s dreams of a new tomorrow can live on, gathering definition and momentum, in the melodies we remember and the songs we sing. Among the many we might recall today, a special place might be reserved for “A Change Is Gonna Come”, written and recorded by Sam Cooke six decades ago, in 1964. Generally regarded – to quote Mike Marqusee – as “the first masterpiece of socially conscious soul”, the song marks a towering peak in a long-running tradition of emancipatory imagining by black artists. Specifically, it preserves the mingled hurt and promise of a pivotal period in the civil rights movement’s nationwide campaign, which James Baldwin among others viewed as an internal “rebellion” comparable in historical significance to the civil war of the previous century.

Cooke’s voice and singing, instantly recognizable, contribute to the track’s overall effect. In the 1950s, as lead-vocalist in The Soul Stirrers, Cooke had risen to fame as a stand-out star in an already virtuosic generation of black singers that included Ray Charles, Jackie Wilson and Harry Belafonte, as well as younger figures such as Etta James and Aretha Franklin – all of whom, to varying degrees, drew on gospel and folk traditions while developing their own distinctive style and repertoire. Whereas Belafonte's voice was lean and clean – a clear tenor, often with a Carribean lilt – Cooke, a gutsy, versatile performer, combined passion and precision over an astonishingly wide vocal range. Perhaps in part due to his childhood as the son of a Baptist minister, his early version of the spiritual, “I'm Going to Build Right on That Shore”, still has the power to tingle the skin. To gain a sense of his talent and charisma, We need only listen to his live recording of Pete Seeger's “If I Had a Hammer” – originally a rousing, anti-McCarthyite protest-piece, later adapted by civil rights campaigners, including the ever-iconic Odetta.

“A Change Is Gonna Come” remains Cooke’s most affecting number. Penned in January, 1964, the track was partly prompted by Bob Dylan’s anti-racist anthem, “Blowin’ in the Wind”, released as a single the previous year. Cooke also drew on his own experience of segregationist hostility, having been refused accommodation in Shreveport, Louisiana, while on-tour with his band in late 1963 (and then placed under arrest by local police officers for supposedly disturbing the peace). Much of the song’s power resides in Cooke’s masterful emotional control, infusing his lyrics with elation and weary yearning – conveying the sheer climb of sustained struggle, against doggedly racist social structures – even as the melody soars in the hope of new horizons, a transformed society. “It’s been a long time coming”, Cooke sings, laying poignant, melismatic emphasis on the “long”: “But I know a change is gonna come”.

When placed against the backdrop of history as it was then unfolding, the refrain rings out as an almost utopian statement of political faith, which nonetheless contains its share of quiet grief. Six months before the song’s composition, in June, 1963, Medgar Evers, leading civil rights campaigner, had been murdered by a Ku Klux Klan member in Mississippi. In the ensuing weeks, a wave of civil disobedience and protest led by black campaigners swept the nation. As Mike Davis and Jon Wiener note, “if mass activism is measured by the sheer number of protests and arrests, the summer of 1963 was unquestionably the high point of the civil rights struggle”, with the Department of Justice cataloguing 1,412 separate demonstrations around the country betweeen June and September. To hear Cooke's song today is to recognise afresh the audacity and combustible desperation of those resistance days, and to feel, also, the shadow and burden of the losses that followed – the long line of civil rights and black power activists who were killed, imprisoned, and silenced, from Martin Luther King Jnr. to Fred Hampton, and beyond. (Sam Cooke himself would die in somewhat lurid, albeit disputed, circumstances in December 1964, two weeks before his soon-to-be-famous track was issued as a single.)

Spike Lee recognised the song's potency in exactly these terms when he used it on the soundtrack of his 1992 biopic, Malcolm X, in his depiction of the lead-up to Malcolm's assassination. The sequence, in which little ostensibly happens, is intensely moving: we observe Malcolm's growing exhaustion, and irrepressible charm, as he goes about his routine of travel and street-talk, before the speaking event that would be his last, at the Audubon Ballroom, Manhattan. “Don't be shocked when I say that I was in prison”, Malcolm had urged audiences in the year before his killing, “You're still in prison. That's what America means: prison.” The grimness, and political courage, encoded into that insight seems to shine in Denzel Washington's features during this scene; we understand the necessity of Malcolm's freedom struggle, and its heavy weight. Layered over such images, moreover, Cooke's soaring, plangent music serves to foreground Malcolm's complexity: his fierce hunger for justice, and his deep humanity – for as James Baldwin later recalled, “he was one of the gentlest people I ever met.”

Such political resonances are amplified by the street-curb eloquence of Cooke’s lyrics, vividly evoking both the cultural richness and the physical dangers of daily black life under the shadow of what Alexander Saxton called “The White Republic”. “I go to the movie and I go downtown”, he sings, “Somebody keep telling me don't hang around. / It's been a long time comin', / But I know a change is gonna come.” In this respect, the song anticipates Marvin Gaye's “Inner City Blues”, with its catalogue of “Hang ups, let downs, / Bad breaks, set backs” faced by black urban populations during the early 1970s. In the latter, the cool, seductive ease of Gaye's singing only heightens the jaggedness of the social portrait he advances – of a modernity at once exploitative and violent, where justice is scarce, and the colour line continues to demarcate American lives in crucial ways:

Yeah, it makes me want to holler,

And throw up both my hands:

Crime is increasing,

Trigger happy policing,

Panic is spreading,

God knows where we're heading.

Needless to say, but such sentiments reverberate painfully today, across a post-Trump (and post-Obama) political landscape defined by seething white supremacist tensions and seemingly unyielding patterns of state violence. In a relevant discussion, the philosopher and Christian socialist Cornel West has argued that the cultural “strivings” of black artists in the United States should be seen as “the creative and complex products of the terrifying African encounter with the absurd in America, and the absurd as America”, a nation founded as “a slaveholding, white-supremacist” society, which nonetheless continues to consider itself “the most enlightened, free, tolerant and democratic experiment in human history.” In the face of such extreme social hypocrisy, and in the train of relentless historical horrors, he writes, the “music” of such artists “leads us – beyond language – to the dark roots of our scream and the celestial hights of our silence.” In their graceful, unflinching freedom verses, both Gaye and Cooke are exemplars of this tradition, which flickers audibly in the opening words of Cooke's song.

“I was born by the river, in a little tent”, Cooke begins, “And just like the river I've been runnin', ever since.” “I was born by a golden river and in the shadow of two great hills, five years after the Emancipation Proclamation”, wrote the legendary intellectual and justice-seeker W.E.B. Du Bois in his memoir, mixing biographical accuracy with a conscious echo of the Jubilee spiritual, “Deep River”. Tracing the tributaries of emotion that course just below the surface of Cooke’s song, we find ourselves on the open plains of a wider world-historical inheritance. “My soul has grown deep like the rivers”, said Langston Hughes:

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and

I've seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

Hughes's poem articulates what Cooke's emancipatory memory-song and rallying-cry also latently expresses, transmuting a litany of suffering and struggle into a wide-spanning vision of political self-possession and spiritual uplift. When we enter the flow of this surging, deep-rooted song, we understand the protean and transformative power that black liberation movements have always had throughout American history. Today, more than ever, “A Change Is Gonna Come” helps us to replenish our sources for the struggle that lies ahead.