- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- Movie Miscellany: 15

- Trump Rant by Chris Agee

- The Invisible Heart: Katie Donovan

- The Letters of Seamus Heaney

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

Movie Miscellany: 1 (Dune, Fort Apache, Iraq in Fragments, Metropolis, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood)

Dune (dir. Denis Villeneuve, 2021)

Timothée Chalamet, lean and mopey, leads an all-star cast (with aplomb) in Denis Villeneuve’s spectacular allegory of imperial hubris and decline. Chalamet’s young dukeling, Paul Atreides, accompanies his father, the thoughtful colonialist Leto (Oscar Isaac), and mother, the mysterious and psychically gifted Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson), to the planet Arrakis, with the aim of ‘managing’ its rich reserves of Spice, while placating the fearsome natives. Machiavellian machinations ensue, and (unlike in Blade Runner 2049) the resulting sequence of conflict and chase is handled with almost balletic assurance and precision. Villeneuve exploits the considerable abilities of his troupe of players to disguise or re-purpose the mono-dimensionality of their characters; Jason Mamoa and Javier Bardem bring gruffness and grandeur to the archetypes they fill, while Zendaya somehow dignifies the task she’s given, of shimmering, intermittently, as the girl of Paul’s dreams. All the while, an epic soundtrack and moody visual design breathe life into Frank Herbert’s epic vision, and its apparent moral: that the inheritors of empire and capital, who consider themselves benign, entitled, and omniscient, must either join the indigenous resistance or face extermination at the hands of their fascist-imperial allies. As such, Villeneuve’s big-screen masterpiece resonates, on our increasingly dune-like Earth.

Fort Apache (dir. John Ford, 1948)

Fort Apache projects a potent and largely fictional image of the American West: in which noble Indians deserve personal respect, while also requiring political annihilation; where rambunctious immigrants (of Irish- and Mexican-American stock) are excluded from the nation’s commemorative self-narrative, even as they are shown to be its courageous and wholesome architects on the ground; and where ambitious, high-ranking militarists are undone by their own elitism and arrogance. The sentimental sympathy extended to the cavalry’s rank-and-file and non-commissioned officers (and, indeed, their wives) may be taken as expressing the tenor of Ford’s patriotism after the second world war. The script also attempts to honour Cochise and Geronimo, eloquent and fierce in their resistance to dispossession (and federal duplicity), at the same time that the narrative deploys racist and genocidist tropes in its imagination of a new society, won through the hard labour of military slaughter. In the warmth and respect he accords to his “men”, their “women”, and the Apaches he hunts, Captain York (John Wayne) is the film’s most sympathetic character, and the most cynical. After risking insubordination by criticising the strategy of his superior, Colonel Thursday (Henry Fonda), on the basis that he had given Cochise his “word” that the Apaches would be treated fairly, York survives to be promoted to commander-in-chief of the regiment at the finish, at which point he lies, knowingly and carefully, to the East Coast reporters who have come to mythologise the new “campaign” he now directs against the same tribes. Although remembered for its populist heroising of the US cavalry, Ford’s film may also be considered iconic in its staging of Thursday’s last stand, when the land thunders, the wind blows with a vision-altering dust, as indigenous warriors out-smart and then overwhelm the decorated murderer, who kills and dies with “glory” on his mind.

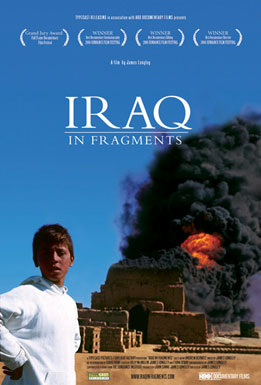

Iraq in Fragments (dir. James Longley, 2007)

Director James Longley spent two years in Iraq making this unflinching, visceral, attentive film, a diagnosis in triptych. First, we encounter Mohammed, an eleven year-old orphan in Baghdad, as he runs the hectic streets. “Why don't they take the oil and leave us alone”, a customer asks at the garage where he works, “Saddam took everything for thirty-five years. Now the Americans will be even worse.” Mohammed’s fierce, listening eyes grow quiet, as the men in the shop, loud with exhaustion, talk on and on. In the South, Mohammed al Sadr is running for election in two Shiite cities. “We are an Islamic city!”, his supporters shout, “We will close every door of depravity opened by America.” A young boy mouths the words of a prayer, day-dreaming, as the crowd behind him kneels and chants; he has the fresh-cropped hair of a child, the expression of an old man. Later, a religious leader pauses, a shadow crossing over his stern, sleepless face: “Who can trust America?”. In the final chapter, “Kurdish Spring”, the time is new, the season bright. A deep daylight trails through the stalks of sunflowers, as a wide-smiling boy, the son of Kurdish farmers, eats the seeds. Nearby, two men sit in the shade, playing draughts with stones. But even here, we learn, politicians grow “fat” and “the poor people are moaning with hunger.”

Metropolis (dir. Fritz Lang, 1927)

With melodramatic exuberance and a dash of Christian millenarianism, Metropolis offers a pulsating parable of industrial society, divided between those who enjoy the freedoms and glamorous frivolities of civilization, and others whose dehumanising toil sustains the rest: “Deep beneath the earth” (we’re told) “lay the City of the Workers.” Lang’s virtuosic vision is thrilling and ingenious, his sense of cinematic scale a thrill to behold, fixing “for the rest of the century”, as Roger Ebert observed, “the image of a futuristic city as a hell of scientific progress and human despair.” When the protagonist Freder (Gustav Fröhlich), the son of a powerful industrialist, goes searching for a mysterious girl from the under-world, he witnesses a factory disaster, and is seized with horror. The immense, frantic hallucination of Moloch that follows, consuming the bodies of the workers, is startling and fresh, an apocalyptic reckoning with the realities (of engineered exploitation and brutality) that hold up Feder’s world. The later, feverish portrayal of elite decadence is likewise self-aware, depicting a swirling modern “Babylon”, undone by its own “sin”. Lang’s implicit distrust of Rotwang the inventor (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), driven by a maniacal desire for social and amorous control, is balanced by his equally potent fear of the masses in heat, charging unbridled towards ruin and disorder. As a result, the film’s admiring portrait of Maria (Brigitte Helm), a latter-day proletarian visionary in the mould of Joan of Arc, is at odds with its hysterical scenes of labour-revolt and Luddite-style militancy (“Death to the machines!”), manipulated from on high by the power-hungry inventor himself. Metropolis gains by these tensions, embroiling us in the lavish, compulsive poetry of its visual style.

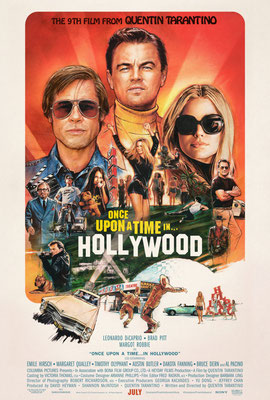

Once Upon a Time… In Hollywood (dir. Quentin Tarantino, 2019)

Depending on what you think of Quentin Tarantino, this meticulous, canny fable of America’s imaginary past is either dazzlingly unique or kitschy, offensive, and dull. A master of his craft, Tarantino has always been easy to imitate, but impossible to match. His great talent has been to bend his medium totally to his own fixations, whether these involve retributive violence, forgotten b-movies, or foot fetishism. This would be limiting only for the fact that the resulting films are so referential and intense they seem, simultaneously, to shatter the grand mirror in which American culture views itself. Such a dynamic is present here, where we follow a has-been (or never-quite-has-been) tv actor, Rick Dalton (Leonardo Di Caprio), and his stunt double (Brad Pitt), as they lollop and chat between movie-sets in late sixties Hollywood, a twilight zone Tarantino conjures with affection, even as he exposes the empty-headed solipsism that lies behind most of its iconography. Once again, the problem with Tarantino is that his obsessions are so relentlessly rehearsed: no matter how sweepingly orchestrated or comically garrulous his movies are, watching them can feel like being stuck in a room with a precocious 14-year-old with mildly sadistic tendencies. Predictably, then, the explosive ending mobilizes our most voyeuristic and vengeful instincts: a re-imagining of the Tate–LaBianca murders that inflicts equal and atrocious violence on the perpetrators, while averting (on-screen) the actual butchery that occurred. This, of course, fulfils the crude calculus of revenge that has obsessed Tarantino since the early ‘90s, while also satisfying Hollywood’s market expectations, which demand, among other things, a finale that is victorious, or at the very least charming. This film is artful, abrasive, nostalgic, and mocking, a mélange that allows Tarantino to have the last, titillated laugh at our expense.