- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

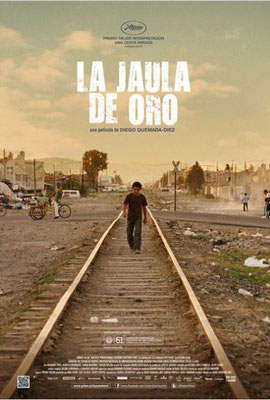

Movie Miscellany: 3 (Land and Freedom, Singin' in the Rain, The Golden Dream, The Purple Rose of Cairo)

Land and Freedom (dir. Ken Loach, 1995)

When Land and Freedom was released in cinemas in October, 1995, Britain’s Labour Party had recently repealed its constitutional commitment to the nationalisation of domestic industries and revised its internal voting procedures, dissipating the traditional influence of its trade union member-blocs. Within months, the bulk of the party’s elected representatives would unite behind the vision of its young leader, Tony Blair, renouncing the “outdated ideology” of decades past in the name of pragmatism, progress, and electoral success: “What counts is what works.” New Labour had arrived. Against this background, Loach’s dramatisation of the radical energies and egalitarian values on the far-left of the Spanish Revolution may be seen, in part, as a powerful subversion of an increasingly dominant paradigm in British (and global) politics. Recounting the experience of the fictional David Carr (Ian Hart), a Communist in 1930s Liverpool who signs up to fight for democracy in Spain, the film offers an up-close-and-personal portrait of the passionate ideals and many hazards of the loyalist militia movement, as socialists and anarchists battle to stave off murderous Francoist aggression and, on their own side, lethal Stalinist power-mongering. The famous assembly scene, when militia-members and local villagers debate the necessity for collectivisation (from the grassroots up), pulses with political fire and a naturalism so intense as to be nearly overwhelming: we forget that these are actors before us, and imagine ourselves to be somehow present in the fractious, scorching moment of the revolutionaries and their struggle. What sort of social liberation would it be that disregards Spain’s “two million landless peasants”, wonders a ruminative Scot (Paul Laverty). Victory against Franco would be pointless, another like-minded militant argues, that allowed poverty, misery, social subjugation to remain in place. By the finish, we understand the world-historical weight of apostasy and compromise in such matters, and feel its weight more intimately still when we recall what Loach has also shown: a huddle of mournful, dust-weary rebels around a newly dug grave, breaking into song as they raise their arms to the sky.

Singin’ in the Rain (dir. Stanley Donen/Gene Kelly, 1952)

A limited actor with a nevertheless unmistakable physical presence, when Gene Kelly starts to dance he blends athletic control with an air of abundant spontaneity and joy; to watch him move, as the rhythm flows from his weaving limbs, is to feel a tidal wave of delight rising in your body, as the world comes into its fullness again. Singin’ in the Rain is arguably the most satisfying of Kelly’s musical hits, less fickle than An American in Paris (1951), more thoughtful than On the Town (1949). As Roger Ebert once remarked, it’s also “a movie about making movies”, and the gentle drubbing of silliness and artifice in Hollywood studio culture adds yet more humour and self-awareness to the film’s already giddy pleasure in its own unfurling. It features, of course, an array of now-classic songs and set-pieces, from the lavish (and luminous) “You Were Meant For Me” to the raucous, pun-pattering slapstick of “Moses Supposes”. Both of Kelly’s co-stars, Debbie Reynolds and Donald O’Connor, have their own elegance and assurance on-screen, which may account for the sheer warmth of the characters they portray: we forget their emotional slenderness, and bask in the brightness they sustain. Singin’ in the Rain itself is much the same: a continuing, unquenchable star-burst of a film, brimming with pitch-perfect, weathery gladness. It reminds us of what cinema can do, and of who we are at heart.

The Golden Dream (dir. Diego Quemada-Díez, 2013)

The years following the release of this film were notable for the escalating numbers of children reported brutalized, abandoned, or dying at the borders of the so-called Global North (Europe and the USA), while news channels filled up with the (by turns) noxious spewing and vacuous mumbling of political leaders whose policies exacerbated such crimes. Centred on two young teenagers from Guatemala, Juan (Brandon López) and Sara (Karen Martínez), and an indigenous boy named Chauk (Rodolfo Domínguez), as they attempt to traverse Mexico and enter the United States, The Golden Dream is grounded, luminous, furious, and humane: a tribute (to its protagonists) and a denunciation (of the world that besieges them). Quemada-Díez shows us the incandescence of young love and friendship; in moments Sara and Chauk seem to speak a dialect comprised only (and miraculously) of tenderness and wonder. Their soft smiles light up the screen. Even as the film acknowledges the radiance and singularity of their lives, however, it continues to track, scrupulously and without evasion, the actualities of race hatred, state authoritarianism, sex trafficking and child-directed abuse that loom on every side of the various political lines they are determined to cross. Previously a camera-man on Ken Loach’s Land and Freedom (1995) and Bread and Roses (2000), Quemada-Díez brings the humanist sensibility and militant consciousness of the Loachian mode to his cinematic canvas here, and in the process forges that rarest of treasures: a sympathetic and character-driven journey-poem, travelling into the heart of its own world-history, which at the same time serves, with unerring clarity and grace, as an accusation of our time, too often shaped, as Quemada-Díez sees, by intimate exploitation and man-made savagery. The huge snows swirling down from blank skies at the film’s close are cold, unfeeling, and strangely beautiful, like a dream that never was.

The Purple Rose of Cairo (dir. Woody Allen, 1985)

Allen’s most fully achieved films immerse us in the bustle and (sometimes goofy) quandaries of hyperactive characters who exist in an insular world they’ve always known, and so think of as natural. At his sharpest, Allen allows the varieties of delusion and narcissism he recognises in his protagonists’ behaviour to cast a cinematic spell, even when the consequences of such indulgence are exposed as dangerous or emotionally damaging as the plot progresses. The Purple Rose of Cairo absorbs and expresses these concerns in what is nonetheless a softly sympathetic portrait of Cecilia (Mia Farrow): a compulsive movie-goer in 1930s New Jersey, who falls for Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels) after he literally steps off the silver screen and into her life. “Love at first sight doesn’t just happen in the movies”, Cecilia explains, matter-of-factly, to her baffled husband (Danny Aiello). “I’m confused”, she later muses, “I’m married. I’ve just met a wonderful new man: he’s fictional, but you can’t have everything.” Tom, of course, has left his chattering fellow film-characters mid-scene, stranded and perplexed as the reels keep turning. “It’s not possible!”, one of them exclaims (in black and white), as Tom strolls into the movie theatre; “I’m in the world of the possible”, he replies, with a cheerful shrug. When a host of studio executives and actual A-listers gets wind of Baxter’s escape into reality, Allen manages to show up what he sees as the mendacity and commercialism of the film industry. Vitally, however, he does so without unsettling the screwball humour and lovely charm of the picture as a whole. The Purple Rose of Cairo critiques the dream-factory that made it, even while paying homage to Cecilia and people like her, who turn to movies looking for (and possibly finding) a sense of romance and magic too often lacking in life itself.